HARMONISING SELF & SPACE

A snippet of my BA Dissertation on the human-physical space dynamics through the lens of Rhythmanalysis.

1.1 Background

As social beings, expressing our identities is a fundamental need that gives us a sense of purpose and safety (Leary et al. 69, 70). We could even go so far as to call this need for “expression” a part of human nature. As grand as it sounds, the act of expressing identity can be seen through seemingly mundane activities, both done consciously and unconsciously, mainly through the use of symbols (GCSE). These symbols can take the form of various things, including the objects that surround us.

As individuals, we construct our identities through choice by paying close attention to things that externalize our image and identity. A study by Kim and Johnson showed that areas of the brain involved in thinking about the self—the medial prefrontal cortex—also appear to be involved whenever humans create associations between our belongings and ourselves through a sense of ownership (199-207). It is a mind-tickling phenomenon that even seemingly insignificant belongings can play a significant role in how we express ourselves. In relation to the formation of identity and self, Japanese performance and installation artist, Chiharu Shiota, brings forth an interesting statement about layers of human identity.

Shiota states that human skin is the first layer in which we were all born in, clothing becomes our second layer, and the house—or in another word, our surroundings—makes up our third and most outer skin (Galerie Templon Brussels, “Inaugural Show By Chiharu Shiota”). Having experience in creating works that interweave materiality and psychic perception of space to explore ideas around personal narratives that engage with memory, territory, and solitude (田千春), this statement by Shiota gives an insightful perspective into the concept of individual identity by bringing it into something less focused on a person’s physical body, instead shifting our perception towards the true nature of expression: that expression isn’t merely seen through presenting the subject (the self), rather it can reflect through the influence of everything around us—our surroundings, our objects, tools, and belongings, and places.

In this paper, we will discuss the interesting enigma in which our environments (the third layer of our identity) form and shift in accordance to patterns of human-object interaction within a personal space. By unraveling the intricacies between the self’s relationship with our possessions, this paper curiously contests the existence of a system of patterns and symbols in space, not only as evidence of how that space can be configured, but as a way to appreciate the luxury of a personal space as an extension of ourselves and as an important aspect of cultivating a positive living environment (Belk 139). From a visual communication perspective, referring to and even challenging established systems and reading patterns as a means for meaning-making is not considered foreign, as it is found in several principles commonly applied by designers in the field, such as semiotics, the application of grid systems, and the Gestalt Theory.

By viewing objects and personal belongings in our surroundings as patterns that correspond to a whole (that is, a person’s identity), this paper opens up other unique pathways in observing and discussing the intricacies of who we all are as people and the potential of the spaces we inhabit.

1.2 Literature Review

This literature review aims to synthesize the main arguments and concepts from relevant readings related to the research topic. The readings are categorized by topic for clarity and structure as follows: 1) Humans and Our Objects, 2) The Importance of Personal Space, 3) Object-Centered Rhythmanalysis in Personal Spaces, and 4) Visualizing Rhythmanalysis. By contrasting and comparing these ideas, this section aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the research topic.

1) Looking at aspects that form the complex interrelationship between humans and their objects.

2) Discussing the importance of personal space and its relation to the individuals that inhabit them.

3) Introducing rhythmanalysis as a “decoder” of everyday life and its application in analyzing personal spaces.

4) How rhythmanalysis work with visual patterns.

Section 1:

Humans and Our Objects

My interest in this research topic was sparked by the book Are We Human? By Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley. Colomina is a Professor of Architecture and founding director of the Media and Modernity program at Princeton University, while Wigley is a Professor of Architecture and Dean Emeritus of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation.This book explores the intrinsic relationship between human and design (designed objects, tools, and artifacts), explored through significant moments in human history. The manner in which this book reads resembles an archaeological record of humanity and its artefacts. Some chapters from Are We Human?—such as ”The Invention of the Human” (51-59), “Good Design is an Anaesthetic” (89-103), and “Human-Centered Design” (127-143)—provide insights into the nature of our relationship with designed objects and tools. The authors argue that what makes humans human is not just our thoughts and physical bodies, but our interdependence on the objects that surround us (Colomina and Wigley 23); that we become humans through seeing ourselves and the possibilities of what we can be as a community and through the things we make (51).

In Are We Human? It is also mentioned that our relationship with our objects are transformative and ever-changing (138), and that humans are inseparable from their artifacts due to various reasons: The things we own and create fulfill necessary functional, sentimental needs. Having always been intimately connected to our objects (241), some of our things can even become part of our sense of self (246). Therefore without it, at times we feel naked or vulnerable (240). Our objects also act as interfaces between the human and the world and it allows us to engage with the world in so many more ways and vice versa (25). In other words, our objects challenge us to creatively navigate the world using each of our personality, experiences, and abilities–all factors that make up who we are as an individual.

Section 2:

Importance of Personal Space

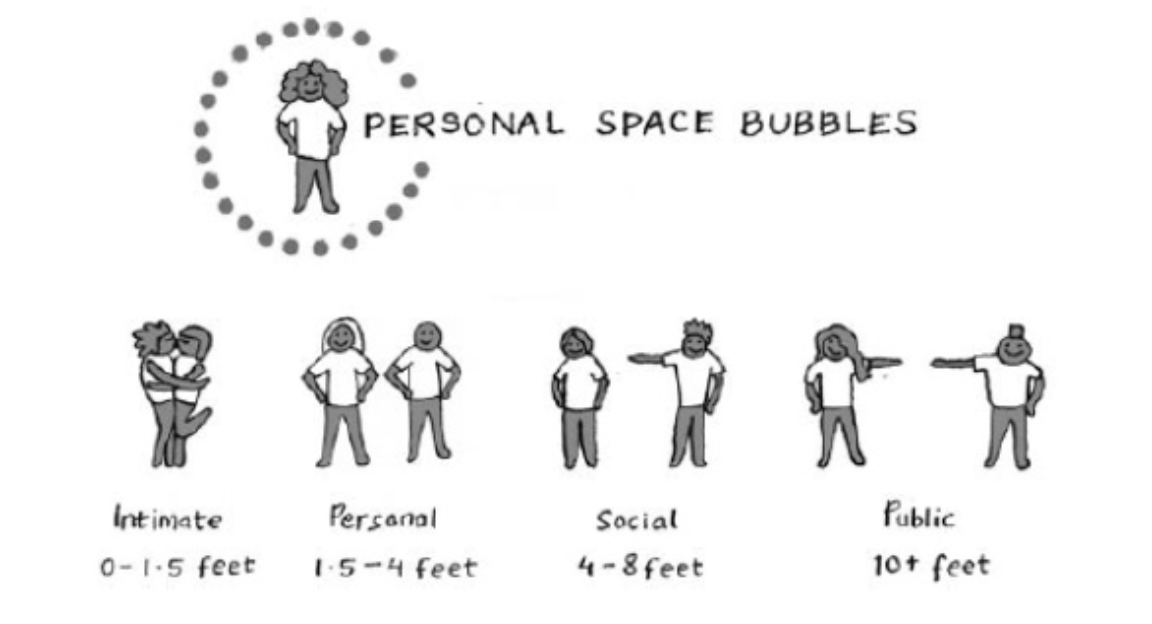

While Are We Human? presents the intricate relationships humans have with their objects and tools through a larger perspective of society, the book Shaping of Us by Lily Bernheimer–a researcher, writer, and consultant in environmental psychology–introduces the reader to the concept of ‘Personal Space Bubble’ and ‘Territory’ (Figure 1.1), arguing that both are critical to our sense of safety and are closely linked to individuality and personality (Bernheimer 48-49).

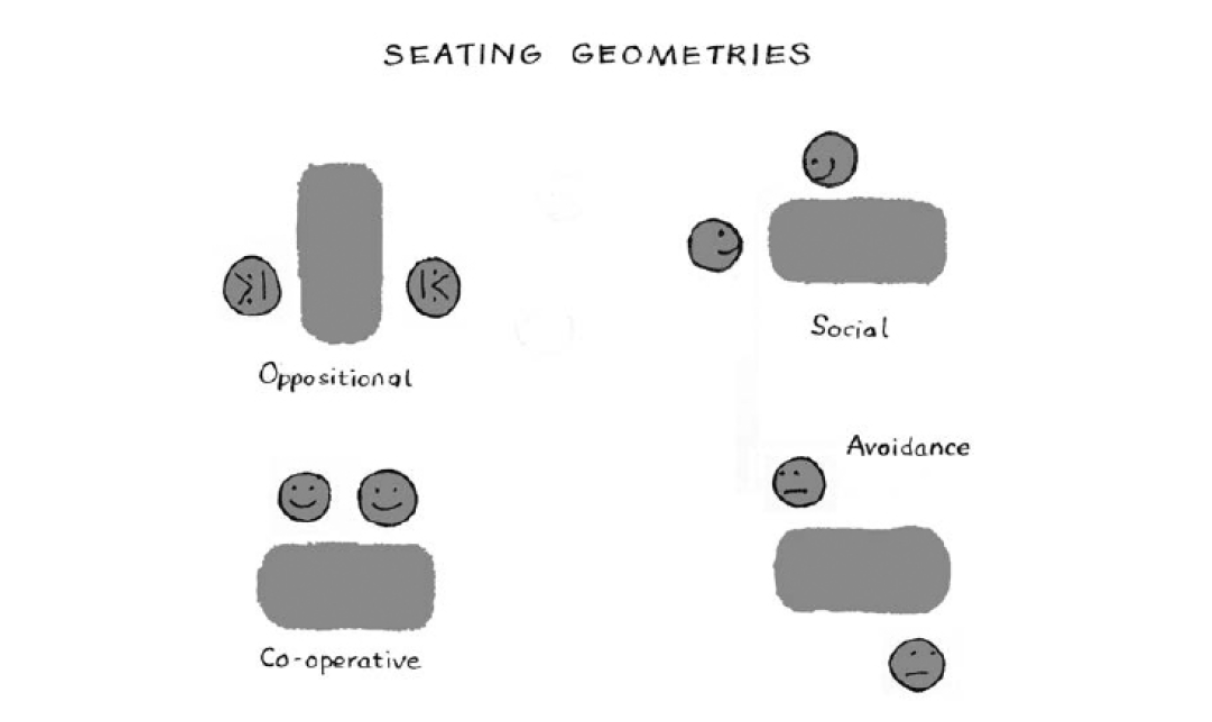

In the chapter “The Defeat of the Ninja-Proof Seat”, Bernheimer discusses the importance of personal space by providing studies and observations (Figure 1.2) on how people interact with other people and objects in several work scenarios in conjunction with the concept of a Personal Bubble and Territory. Through her case studies, Bernheimer strongly argues in favor of building personal workspaces that can work for every individual’s personality through allowing privacy–both visual and sound privacy and autonomy (55). As Bernheimer states, “Allowing people freedom of their own personal space creates places people are attracted to. Spaces that feel like places instead of fuzzy gray boxes.”(68).

In relation to the importance of space to a person’s sense of self, it is evident that personal space is listed as one of the spaces which contains objects that act as reminders and confirmers of our identities, and that our identities may reflect more through our own objects within that space rather than other individuals. This evidence relates back to the chapter in Shaping of Us, which states that inanimate objects breach our ‘personal bubbles’ more easily than people around us (Bernheimer 47). In other words, humans are more likely to interact and develop a bond with objects which could enter their ‘personal space bubble’. By paying attention to the criteria of a ‘Personal Space Bubble’ and ‘Territory’ to our workspaces, we can create places people can freely be themselves in.

Additionally, little acts of personalisation in your own space does reflect the identity of the person who occupies it (49). This act of personalisation can be done through decoration, rearrangement, or adaptation of objects in a specific area. In conclusion, points from the readings have brought forth factors supporting the importance of privacy, safety, and autonomy for our sense of self, which successfully highlights the importance of personal space and how it is a luxury to be able to craft a space one self is truly in control of.

Section 3:

Object-centered Rhythmanalysis in Personal Spaces

In search for a structured method to tie the concept of Human-Object Interactions and ‘identity expression’ together. I took inspiration from Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life by Henri Lefebvre, followed up by Thoughtless Acts? by Jane Fulton Suri from IDEO, a global design innovation company focusing on human-centered design solutions. In Rhythmanalysis,the core takeaway would be its introduction of rhythmanalysis as a concept. Lefebvre argues that rhythm is present everywhere there is interaction between place, time, and expenditure of energy (26).

This statement supports the notion that formation of rhythm occurs naturally during our day-to-day activities, including the objects involved in those activities. Rhythm occurs and beats dynamically and are closely connected to other rhythms through the influence of social environments and routines of our personal lives (9). Understanding everyday moments through rhythm helps simplify this web of connections by dividing it into smaller moments/’presences’ (23).

In addition, the book Rhythmanalysis illustrates variables that contribute to the making of rhythms, such as repetition, interferences, and flow (25). When talking about rhythms in relation to everyday lives, Lefebvre stated that by understanding rhythms of our bodies and the environment, we gain a privileged insight into the questions of the mundane (6). Playing with the abstract and representing it with a concretely readable result would be a viable method of research to understand the building blocks of human-object interaction in relation to the space it occurs in.

In Thoughtless Acts?, Jane Fulton Suri prompted the question of how designers can improve their work through observing visual cues seen in unconventional acts done towards designed objects and systems in place. Concluding insights from Thoughtless Acts? proves the versatility of human-object interactions. This is an interesting phenomena which questions the predetermined boundaries and expectations of how we can interact with our objects besides its original intended use.

Going back to analysis of rhythms, Reintroducing more of Lefebvre’s Rhythmanalysis to analyze human-object interactions encourages the mind to think of the many “thoughtless” acts as patterns, fitting seemingly random acts into its categories by following patterns of repetition, interferences, and flow within groups of “thoughtless” acts. When comparing Thoughtless Acts? to Rhythmanalysis, noticing and highlighting these unconventional acts towards everyday objects can be an example for designers on the application of Rhythmanalysis to observe everyday scenarios.

Combining the concepts that these two readings introduced successfully anchors the research towards an object-centered observation; a more visually-focused way of analyzing rhetorics/cues in mundane everyday presences. Keeping in mind the takeaways from these readings will significantly support decision-making on which specific aspects are relevant to be analyzed within one scenario and which kind of actions to pay attention to when extracting a rhythm/pattern.

This introduction of rhythmanalysis towards human acts isn’t baseless, as Suri herself has intuitively applied it in her book to create categories for every act collected. As also mentioned previously, the rhythmanalyst transforms everything into presences (23), including taking parts of the present (such as these “thoughtless” acts) and extracting their meaning (22).

The present should not merely be understood as what they are constituted of, but as symbolic representations of other things related to that present (7). In this way, rhythmanalysis can be introduced as a method focused on observation-based meaning making; one that draws information from visible external sources.

As a rhythmanalyst, Lefebvre encourages the readers to string together visible similarities and differences, therefore clarifying a sense of harmony that is more easily understood (8). For example, mapping out a person’s favorite piece of clothing or sorting a folder book with various jumbled topics becomes easier and more structured through the lens of rhythmanalysis, as it emphasizes pattern-finding from visible information. Therefore, this method would be beneficial in providing a structured way of highlighting the mundane/the overlooked, hence gaining a deeper understanding of our relationships with our things.

The last factor which comes into play is what kinds of ‘presences’ to be analyzed. Everyday life consists of various strings of ‘presences’ happening simultaneously in various places. However, as the highlight of this research is on the expression of identity, this paper will focus on those ‘presences’ that are intrinsically related to the manifestation of the self in the real world. Having decided on an object-centered observation as well, the research leans more toward observing ‘presences’ wherein a group/different groups of objects and possessions are involved. As previously mentioned, Shaping of Us has introduced the readers to ‘Personal Space Bubbles’ and ‘Territory’, stating that both are critically linked to individuality and personality (49). Therefore, applying rhythmanalysis as a tool for object-centered observation in our personally-inhabited spaces will be an excitingly feasible route to take the research further.

Section 4:

Visualizing Rhythmanalysis

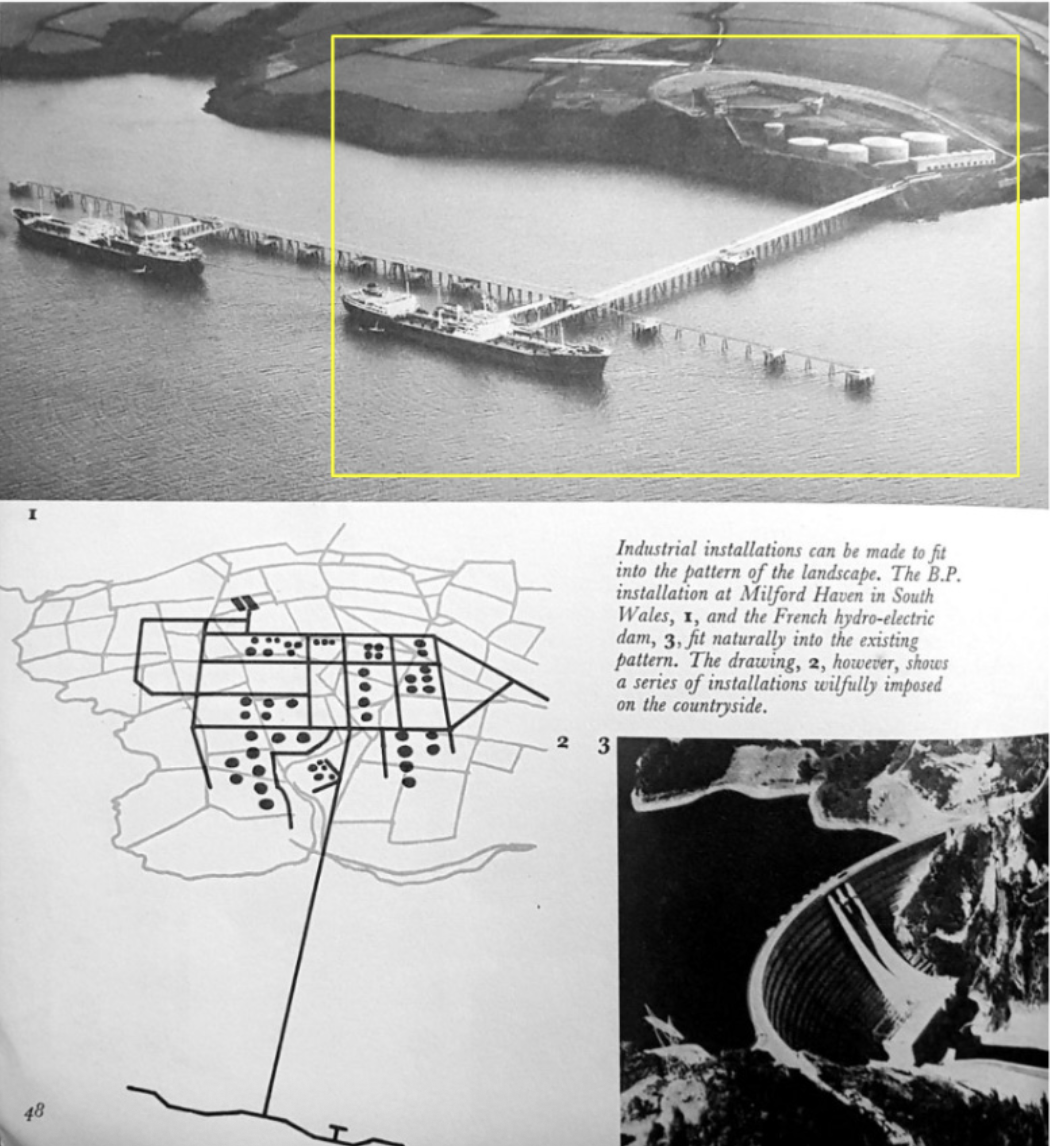

In the previous section, we established the effectiveness of adapting rhythmanalysis as a concept to explore patterns and rhythms of our personal spaces. However, patterns don’t only exist in the conceptual realm; they also exist in visible forms within our surroundings and ourselves. In the book Pattern and Shape, Kurt Roland presents a way of seeing the world by examining visible patterns in nature, man-made objects, and a combination of both. He analyzes how the form of these patterns relates to their visual impact through functionality, effectiveness, decorative qualities, and character (Roland 3).

This approach aligns with rhythmanalysis, as it involves finding patterns in presences that uncover a deeper meaning.Roland acknowledges that patterns are related to culture, a community’s living conditions (10), and evolve with the environment (27). Furthermore, because visible patterns are closely related to rhythm, concepts from the book Rhythmanalysis can be readily adapted into something visible or tangible instead of always viewed as heavily conceptual or philosophical.

Another insight from Pattern and Shape is that it encourages curiosity for an overview of patterns formed by clusters of objects in their surroundings, rather than solely focusing on patterns in one object’s form. For example, one can determine the effectiveness of a man-made landscape by examining patterns it creates on an area of land from above.

In Rhythmanalysis, Lefebvre suggests that to analyze rhythm, we must distance ourselves from the moment or place where it occurs (44). By examining ‘object-filled presences’ through overviews (as seen in fig. 1.4.), we create the necessary distance to analyze them effectively. This act of looking at groups of objects as one ‘presence’ aligns with the configuration of perceived ‘wholes’ and ‘laws of organization’ in Gestalt theory. Within these groupings, we can interpret meaning by identifying perceived visual patterns from a distance and looking at the whole ‘presence’ to identify similarities, interferences, and flow in the configuration of the elements inside (such as object proximity, symmetry, and other elements found in Gestalt theory of perception).

In conclusion, looking at these examples highlights a visually interesting way of analyzing rhythms in our surroundings without focusing solely on singular objects, but rather on groupings and overviews to interpret meaning.

As social beings, expressing our identities is a fundamental need that gives us a sense of purpose and safety (Leary et al. 69, 70). We could even go so far as to call this need for “expression” a part of human nature. As grand as it sounds, the act of expressing identity can be seen through seemingly mundane activities, both done consciously and unconsciously, mainly through the use of symbols (GCSE). These symbols can take the form of various things, including the objects that surround us.

As individuals, we construct our identities through choice by paying close attention to things that externalize our image and identity. A study by Kim and Johnson showed that areas of the brain involved in thinking about the self—the medial prefrontal cortex—also appear to be involved whenever humans create associations between our belongings and ourselves through a sense of ownership (199-207). It is a mind-tickling phenomenon that even seemingly insignificant belongings can play a significant role in how we express ourselves. In relation to the formation of identity and self, Japanese performance and installation artist, Chiharu Shiota, brings forth an interesting statement about layers of human identity.

Shiota states that human skin is the first layer in which we were all born in, clothing becomes our second layer, and the house—or in another word, our surroundings—makes up our third and most outer skin (Galerie Templon Brussels, “Inaugural Show By Chiharu Shiota”). Having experience in creating works that interweave materiality and psychic perception of space to explore ideas around personal narratives that engage with memory, territory, and solitude (田千春), this statement by Shiota gives an insightful perspective into the concept of individual identity by bringing it into something less focused on a person’s physical body, instead shifting our perception towards the true nature of expression: that expression isn’t merely seen through presenting the subject (the self), rather it can reflect through the influence of everything around us—our surroundings, our objects, tools, and belongings, and places.

In this paper, we will discuss the interesting enigma in which our environments (the third layer of our identity) form and shift in accordance to patterns of human-object interaction within a personal space. By unraveling the intricacies between the self’s relationship with our possessions, this paper curiously contests the existence of a system of patterns and symbols in space, not only as evidence of how that space can be configured, but as a way to appreciate the luxury of a personal space as an extension of ourselves and as an important aspect of cultivating a positive living environment (Belk 139). From a visual communication perspective, referring to and even challenging established systems and reading patterns as a means for meaning-making is not considered foreign, as it is found in several principles commonly applied by designers in the field, such as semiotics, the application of grid systems, and the Gestalt Theory.

By viewing objects and personal belongings in our surroundings as patterns that correspond to a whole (that is, a person’s identity), this paper opens up other unique pathways in observing and discussing the intricacies of who we all are as people and the potential of the spaces we inhabit.

1.2 Literature Review

This literature review aims to synthesize the main arguments and concepts from relevant readings related to the research topic. The readings are categorized by topic for clarity and structure as follows: 1) Humans and Our Objects, 2) The Importance of Personal Space, 3) Object-Centered Rhythmanalysis in Personal Spaces, and 4) Visualizing Rhythmanalysis. By contrasting and comparing these ideas, this section aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the research topic.

1) Looking at aspects that form the complex interrelationship between humans and their objects.

2) Discussing the importance of personal space and its relation to the individuals that inhabit them.

3) Introducing rhythmanalysis as a “decoder” of everyday life and its application in analyzing personal spaces.

4) How rhythmanalysis work with visual patterns.

Section 1:

Humans and Our Objects

My interest in this research topic was sparked by the book Are We Human? By Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley. Colomina is a Professor of Architecture and founding director of the Media and Modernity program at Princeton University, while Wigley is a Professor of Architecture and Dean Emeritus of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation.This book explores the intrinsic relationship between human and design (designed objects, tools, and artifacts), explored through significant moments in human history. The manner in which this book reads resembles an archaeological record of humanity and its artefacts. Some chapters from Are We Human?—such as ”The Invention of the Human” (51-59), “Good Design is an Anaesthetic” (89-103), and “Human-Centered Design” (127-143)—provide insights into the nature of our relationship with designed objects and tools. The authors argue that what makes humans human is not just our thoughts and physical bodies, but our interdependence on the objects that surround us (Colomina and Wigley 23); that we become humans through seeing ourselves and the possibilities of what we can be as a community and through the things we make (51).

In Are We Human? It is also mentioned that our relationship with our objects are transformative and ever-changing (138), and that humans are inseparable from their artifacts due to various reasons: The things we own and create fulfill necessary functional, sentimental needs. Having always been intimately connected to our objects (241), some of our things can even become part of our sense of self (246). Therefore without it, at times we feel naked or vulnerable (240). Our objects also act as interfaces between the human and the world and it allows us to engage with the world in so many more ways and vice versa (25). In other words, our objects challenge us to creatively navigate the world using each of our personality, experiences, and abilities–all factors that make up who we are as an individual.

Section 2:

Importance of Personal Space

While Are We Human? presents the intricate relationships humans have with their objects and tools through a larger perspective of society, the book Shaping of Us by Lily Bernheimer–a researcher, writer, and consultant in environmental psychology–introduces the reader to the concept of ‘Personal Space Bubble’ and ‘Territory’ (Figure 1.1), arguing that both are critical to our sense of safety and are closely linked to individuality and personality (Bernheimer 48-49).

In the chapter “The Defeat of the Ninja-Proof Seat”, Bernheimer discusses the importance of personal space by providing studies and observations (Figure 1.2) on how people interact with other people and objects in several work scenarios in conjunction with the concept of a Personal Bubble and Territory. Through her case studies, Bernheimer strongly argues in favor of building personal workspaces that can work for every individual’s personality through allowing privacy–both visual and sound privacy and autonomy (55). As Bernheimer states, “Allowing people freedom of their own personal space creates places people are attracted to. Spaces that feel like places instead of fuzzy gray boxes.”(68).

In relation to the importance of space to a person’s sense of self, it is evident that personal space is listed as one of the spaces which contains objects that act as reminders and confirmers of our identities, and that our identities may reflect more through our own objects within that space rather than other individuals. This evidence relates back to the chapter in Shaping of Us, which states that inanimate objects breach our ‘personal bubbles’ more easily than people around us (Bernheimer 47). In other words, humans are more likely to interact and develop a bond with objects which could enter their ‘personal space bubble’. By paying attention to the criteria of a ‘Personal Space Bubble’ and ‘Territory’ to our workspaces, we can create places people can freely be themselves in.

Additionally, little acts of personalisation in your own space does reflect the identity of the person who occupies it (49). This act of personalisation can be done through decoration, rearrangement, or adaptation of objects in a specific area. In conclusion, points from the readings have brought forth factors supporting the importance of privacy, safety, and autonomy for our sense of self, which successfully highlights the importance of personal space and how it is a luxury to be able to craft a space one self is truly in control of.

Section 3:

Object-centered Rhythmanalysis in Personal Spaces

In search for a structured method to tie the concept of Human-Object Interactions and ‘identity expression’ together. I took inspiration from Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life by Henri Lefebvre, followed up by Thoughtless Acts? by Jane Fulton Suri from IDEO, a global design innovation company focusing on human-centered design solutions. In Rhythmanalysis,the core takeaway would be its introduction of rhythmanalysis as a concept. Lefebvre argues that rhythm is present everywhere there is interaction between place, time, and expenditure of energy (26).

This statement supports the notion that formation of rhythm occurs naturally during our day-to-day activities, including the objects involved in those activities. Rhythm occurs and beats dynamically and are closely connected to other rhythms through the influence of social environments and routines of our personal lives (9). Understanding everyday moments through rhythm helps simplify this web of connections by dividing it into smaller moments/’presences’ (23).

In addition, the book Rhythmanalysis illustrates variables that contribute to the making of rhythms, such as repetition, interferences, and flow (25). When talking about rhythms in relation to everyday lives, Lefebvre stated that by understanding rhythms of our bodies and the environment, we gain a privileged insight into the questions of the mundane (6). Playing with the abstract and representing it with a concretely readable result would be a viable method of research to understand the building blocks of human-object interaction in relation to the space it occurs in.

In Thoughtless Acts?, Jane Fulton Suri prompted the question of how designers can improve their work through observing visual cues seen in unconventional acts done towards designed objects and systems in place. Concluding insights from Thoughtless Acts? proves the versatility of human-object interactions. This is an interesting phenomena which questions the predetermined boundaries and expectations of how we can interact with our objects besides its original intended use.

Going back to analysis of rhythms, Reintroducing more of Lefebvre’s Rhythmanalysis to analyze human-object interactions encourages the mind to think of the many “thoughtless” acts as patterns, fitting seemingly random acts into its categories by following patterns of repetition, interferences, and flow within groups of “thoughtless” acts. When comparing Thoughtless Acts? to Rhythmanalysis, noticing and highlighting these unconventional acts towards everyday objects can be an example for designers on the application of Rhythmanalysis to observe everyday scenarios.

Combining the concepts that these two readings introduced successfully anchors the research towards an object-centered observation; a more visually-focused way of analyzing rhetorics/cues in mundane everyday presences. Keeping in mind the takeaways from these readings will significantly support decision-making on which specific aspects are relevant to be analyzed within one scenario and which kind of actions to pay attention to when extracting a rhythm/pattern.

This introduction of rhythmanalysis towards human acts isn’t baseless, as Suri herself has intuitively applied it in her book to create categories for every act collected. As also mentioned previously, the rhythmanalyst transforms everything into presences (23), including taking parts of the present (such as these “thoughtless” acts) and extracting their meaning (22).

The present should not merely be understood as what they are constituted of, but as symbolic representations of other things related to that present (7). In this way, rhythmanalysis can be introduced as a method focused on observation-based meaning making; one that draws information from visible external sources.

As a rhythmanalyst, Lefebvre encourages the readers to string together visible similarities and differences, therefore clarifying a sense of harmony that is more easily understood (8). For example, mapping out a person’s favorite piece of clothing or sorting a folder book with various jumbled topics becomes easier and more structured through the lens of rhythmanalysis, as it emphasizes pattern-finding from visible information. Therefore, this method would be beneficial in providing a structured way of highlighting the mundane/the overlooked, hence gaining a deeper understanding of our relationships with our things.

The last factor which comes into play is what kinds of ‘presences’ to be analyzed. Everyday life consists of various strings of ‘presences’ happening simultaneously in various places. However, as the highlight of this research is on the expression of identity, this paper will focus on those ‘presences’ that are intrinsically related to the manifestation of the self in the real world. Having decided on an object-centered observation as well, the research leans more toward observing ‘presences’ wherein a group/different groups of objects and possessions are involved. As previously mentioned, Shaping of Us has introduced the readers to ‘Personal Space Bubbles’ and ‘Territory’, stating that both are critically linked to individuality and personality (49). Therefore, applying rhythmanalysis as a tool for object-centered observation in our personally-inhabited spaces will be an excitingly feasible route to take the research further.

Section 4:

Visualizing Rhythmanalysis

In the previous section, we established the effectiveness of adapting rhythmanalysis as a concept to explore patterns and rhythms of our personal spaces. However, patterns don’t only exist in the conceptual realm; they also exist in visible forms within our surroundings and ourselves. In the book Pattern and Shape, Kurt Roland presents a way of seeing the world by examining visible patterns in nature, man-made objects, and a combination of both. He analyzes how the form of these patterns relates to their visual impact through functionality, effectiveness, decorative qualities, and character (Roland 3).

This approach aligns with rhythmanalysis, as it involves finding patterns in presences that uncover a deeper meaning.Roland acknowledges that patterns are related to culture, a community’s living conditions (10), and evolve with the environment (27). Furthermore, because visible patterns are closely related to rhythm, concepts from the book Rhythmanalysis can be readily adapted into something visible or tangible instead of always viewed as heavily conceptual or philosophical.

Another insight from Pattern and Shape is that it encourages curiosity for an overview of patterns formed by clusters of objects in their surroundings, rather than solely focusing on patterns in one object’s form. For example, one can determine the effectiveness of a man-made landscape by examining patterns it creates on an area of land from above.

In Rhythmanalysis, Lefebvre suggests that to analyze rhythm, we must distance ourselves from the moment or place where it occurs (44). By examining ‘object-filled presences’ through overviews (as seen in fig. 1.4.), we create the necessary distance to analyze them effectively. This act of looking at groups of objects as one ‘presence’ aligns with the configuration of perceived ‘wholes’ and ‘laws of organization’ in Gestalt theory. Within these groupings, we can interpret meaning by identifying perceived visual patterns from a distance and looking at the whole ‘presence’ to identify similarities, interferences, and flow in the configuration of the elements inside (such as object proximity, symmetry, and other elements found in Gestalt theory of perception).

In conclusion, looking at these examples highlights a visually interesting way of analyzing rhythms in our surroundings without focusing solely on singular objects, but rather on groupings and overviews to interpret meaning.

“...expression isn’t merely seen through presenting the subject (the self), rather it can reflect through the influence of everything around us—our surroundings, our objects, tools, and belongings, and places.”

“Our objects challenge us to creatively navigate the world using each of our personality, experiences, and abilities–all factors that make up who we are as an individual.”

(Fig. 1.1.) Different distances in personal spaces communicating interpersonal relationships. (BERNHEIMER, LILY. Shaping of US: How Everyday Spaces Structure Our Lives, Behavior, and Well-Being. TRINITY UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2022, pp. 47.)

(Fig. 1.2.) Seating arrangements (left) and seating styles on the work desk (right) shows communicative aspects within personal spaces. (BERNHEIMER, LILY. Shaping of US: How Everyday Spaces Structure Our Lives, Behavior, and Well-Being. TRINITY UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2022, pp. 54-65.)

“The present should not merely be understood as what they are constituted of, but as symbolic representations of other things related to that present (7). In this way, rhythmanalysis can be introduced as a method focused on observation-based meaning making; one that draws information from visible external sources. “

“Kurt Roland presents a way of seeing the world by examining visible patterns in nature, man-made objects, and a combination of both.”

(Fig. 1.3.) Man-made industrial pattern imposed on a landscape, therefore erasing the natural characteristics. (Rowland,Kurt. Pattern and Shape. Ginn and Co., 1981, pp.45.)

(Fig. 1.4.) Man-made pattern imposed on a landscape in a way that fits in the natural flow of the original land. (Rowland, Kurt. Pattern and Shape. Ginn and Co., 1981, pp.48.)

OTHER WORKS

IN THIS CATEGORY

︎︎︎ We Will Find Our Way Home

( An essay about Home and

feelings associated around Home. )

︎︎︎ Thoughts On Art

( A reflexive essay on what

Art truly is at its essence. )

IN THIS CATEGORY

︎︎︎ We Will Find Our Way Home

( An essay about Home and

feelings associated around Home. )

︎︎︎ Thoughts On Art

( A reflexive essay on what

Art truly is at its essence. )